Is the starting position really that complex? The answer is more complicated than a simple yes or no. And the complexity grows as the student learns more.

Is the starting position really that complex? The answer is more complicated than a simple yes or no. And the complexity grows as the student learns more.

Winning Chess Openings, by Yasser Seirawan

Welcome to the August issue. This month we will explore some ideas, quips, anecdotes, complexities, and classic writings about Posture, the rough Japanese translation of which is "Kamai."

I hope you find it interesting and worthy of your time. I also hope to hear from you and to get your feedback.

Faithfully,

Scot Lynch

Yondan, Tsugiashi-do Ju-Jitsu

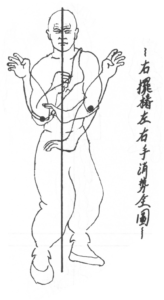

![]() As a rule, if you ready your Kamae at all times, your life will be safe. If violence is suddenly acted upon you, you can be ready to react immediately with the secret techniques of Hakko-ryu.

As a rule, if you ready your Kamae at all times, your life will be safe. If violence is suddenly acted upon you, you can be ready to react immediately with the secret techniques of Hakko-ryu.

Hakko ryu First Degree Manual of Secret Technique

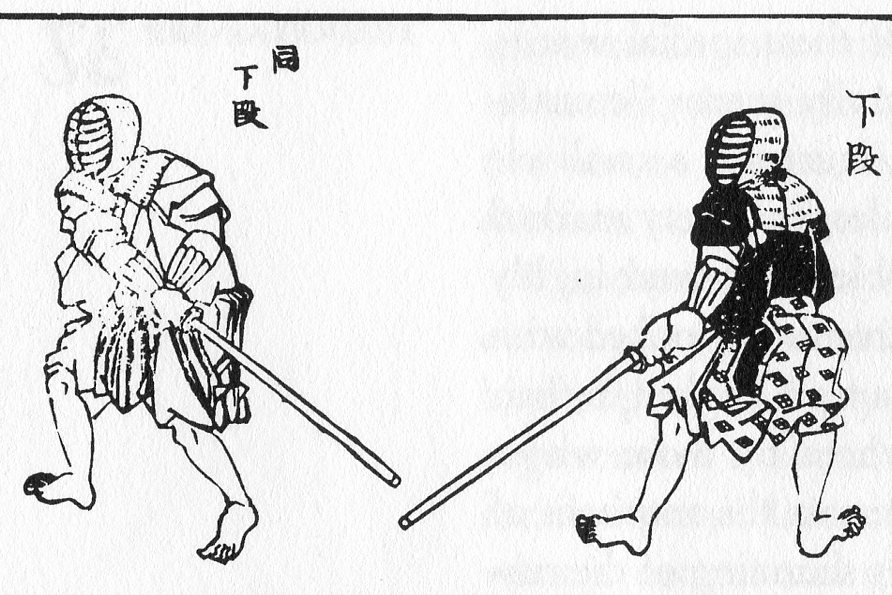

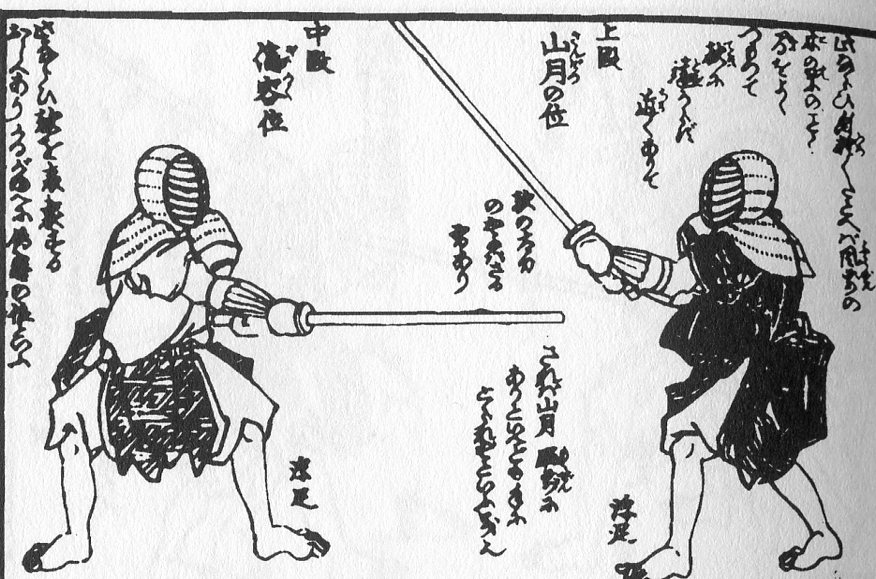

![]() In the widest sense, kamae are intelligible symbols based on physical form (stance, posture, demeanor, general physical attitude) by means of which warriors intuitively came to know something else: for example, whether the enemy was dominantly either aggressive or defensive, his state of confidence, as well as his degree of skill in combat.

In the widest sense, kamae are intelligible symbols based on physical form (stance, posture, demeanor, general physical attitude) by means of which warriors intuitively came to know something else: for example, whether the enemy was dominantly either aggressive or defensive, his state of confidence, as well as his degree of skill in combat.

Classical Budo, by Donn F. Draeger, pp 40

In many ways, a parallel to "kamai", "stance", or "posture" in martial arts is the "opening" in chess: a formal set of beginning moves designed to position the pieces for maximum attacking while maintaining a strong defense of the vital pieces.

![]()

Opening play can contribute towards the checkmating goal in a minor way: Essentially, it can do so by laying a sound foundation for the middle and endgame; by gaining small positional and material advantages. Many small advantages add up to a large plus.

How to Win in the Chess Openings, by Israel Horowitz

Good Reads

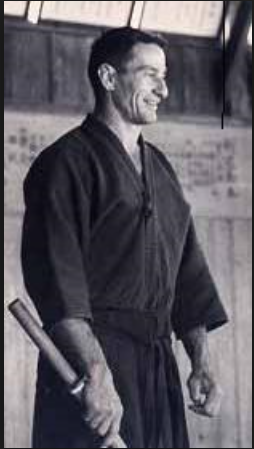

This month’s “good read” is part of a trilogy from Donn F. Draeger, called “Classical Budo.” Draeger was a United States Marine officer, commissioned in the middle of WWII and later fought in the Korean conflict. All three books were put into my hands by Sensei Gabriel Perez (another Marine officer) with a “strong” suggestion to read them. I have been referring to them and quoting them ever since.

According to Wikipedia:

Draeger became a member of the Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai, the oldest Japanese cultural organization for the study and preservation of classical martial arts. He was the first non-Japanese practitioner of Tenshin Shōden Katori Shintō-ryū, achieving instructor status (kyoshi menkyo) in that system. He also held high ranks in Shindo Muso-ryu jodo, kendo, and aikido, among other arts.

Draeger studied the evolution and development of human combative behavior and was director of the International Hoplology Society (IHC) in Tokyo until his death in 1982. These books are profound and rich not just in ancient history of budo, but also of modern budo and the changes that took place during the 20th Century. His accounts are not just researched, many are also first-hand.

This month’s selection, Classical Budo, is featured as it is a rich source of information on “Kamae.”

Perhaps the most essential single element of physical form, as one aspect of the classical disciplines, is kamae, or combative engagement postures. Kamae are valuative in that they help the user to adopt the most appropriate behavior in a given situation. At the same time, they may be incisive signs, for if they are correctly interpreted by the viewer they become symbols that determine how they viewer must act.

pp 39

In the widest sense, kamae are intelligible symbols based on physical form (stance, posture, demeanor, general physical attitude) by means of which warriors intuitively came to know something else: for example, whether the enemy was dominantly either aggressive or defensive, his state of confidence, as well as his degree of skill in combat.

pp 40

Zanshin: alertness remaining-form; continued domination over the opponent characterized by complete, continuous concentration and evinced through both mental attitude and physical posture.

pp 68

…zanshin, the ability of an exponent to gain dominance over an opponent through an alert state of mind and the maintenance of proper physical posture.

pp 131

Controlling The Center

![]() Control of the central squares is the primary positional advantage sought for the opening. It enhances the player’s mobility and operating space to the detriment of the opponent. Exploitation of structural weaknesses pertaining to Pawns is a subsidiary of the opening.

Control of the central squares is the primary positional advantage sought for the opening. It enhances the player’s mobility and operating space to the detriment of the opponent. Exploitation of structural weaknesses pertaining to Pawns is a subsidiary of the opening.

How to Win in the Chess Openings, by Israel Horowitz

Master Bruce Lee may not have played chess, but there are many similarities and parallels between Bruce Lee's writings and chess instructional texts. And for that matter, the Tsugiashi Do manuals.

The fighting measure is also governed by the amount of target to be protected (i.e.: the targets the adversary stresses) and the parts of the body which are most easily within the adversary's reach.

The Tao of Jeet Kune Do, by Bruce Lee

Elbows close to the body control the situation.

Shodai Sensei Richard Faustini, founder of the Heiho Shindo style

Adopt a stance with the head erect, neither hanging down, nor looking up, nor twisted. Your forehead and the space between your eyes should not be wrinkled. Do not roll your eyes nor allow them to blink, but slightly narrow them. With your features composed, keep the line of your nose straight with a feeling of slightly flaring your nostrils. Hold the line of the rear of the neck straight: instill vigour into your hairline, and in the same way from the shoulders down through your entire body. Lower both shoulders and, without the buttocks jutting out, put strength into your legs from the knees to the tips of your toes. Brace your abdomen so that you do not bend at the hips.“

The Onions of Posture: One Size Does Not Fit All

Circa 1980, Yoshitsune Dojo, Closter, New Jersey, the annual 2-day seminar with all the lead instructors taking their turns at leading a class. “O Sensei,” Shihan Michael DePasquale Sr. began the day, giving over to other senior instructors. Late during the second day, Arnold DePasquale, elder son of “Big Mike” took his turn at instructing the taikai. I believe he was fourth or fifth dan at the time. I was a white, perhaps a yellow belt. I remember him teaching several varieties of leg sweeps and throws. Arnold was a long, lanky man, perhaps 6’3” or 6’4”. When he spoke, heads nodded, and bodies flew. We practiced a bit, and then took a break while Arnold went back to his office, behind the karate deck. One or two more instructors went through their lessons, and the last up for the day was a guy I didn’t know very well, wearing a strange purple and red belt. I figured he was a senior instructor. After all, he and Mr. DePascuale called each other by first name.

“Doc” Cohe, as I was to learn his name, demonstrated some moves that were probably over my head. But then he asked us all to sit down in a comfortable position. It was a hot, long and exhausting day and I remember being very glad for the rest. Doc explained that there  simply cannot be any secret moves that are passed down hundreds of years through generations, for the simple reason that there are too many variables in the way people are put together (height, weight, length of limb, center of gravity, flexibility, as well as any physical weaknesses or injuries). And these differences are critical for both Uke and Tori, and that not every move works the same way for every person on every attacker. And it logically follows that there are no “ancient techniques” that can be “handed down” from generation to generation. It just ain’t so. I suppose he was being met with blank stares, because he called someone over to demonstrate a move to make his point. But not in the way we all thought he would.

simply cannot be any secret moves that are passed down hundreds of years through generations, for the simple reason that there are too many variables in the way people are put together (height, weight, length of limb, center of gravity, flexibility, as well as any physical weaknesses or injuries). And these differences are critical for both Uke and Tori, and that not every move works the same way for every person on every attacker. And it logically follows that there are no “ancient techniques” that can be “handed down” from generation to generation. It just ain’t so. I suppose he was being met with blank stares, because he called someone over to demonstrate a move to make his point. But not in the way we all thought he would.

He chose one of the blackbelt instructors, Pat Rafiel, and asked him to throw a punch. The man in the red and purple belt attempted to perform the same move performed just a couple of sessions before, but it didn’t seem to work right. Which, of course, was the point. What I would come to understand later, was that Shihan Cohe was not just a ju-jitsu player who could thwart attacks, make people tap out in pain, and throw them around effortlessly. Shihan Cohe could look into a student’s eyes and know if they had understood the concepts or if they didn’t. What I did not fully grasp that day in 1980, was that we were in the hands of a professionally trained educator, a rarity in the martial arts.

He explained that Sensei Rafiel was too tall, his arms too long, and the wrong leg was forward and the wrong leg was back for him to do the prescribed move effectively. This “Doc” Cohe paused for effect, looked at each of us, raised his voice, and said incredulously “You’d have to be Arnold DePascuale to make this move!” Now heads were really nodding, because we remember Arnold, all 6 feet 3 inches of him, performing the same move effortlessly.

Even to a white belt, that made perfect sense. And like a true educator, it started me on a long road to questioning “ancient techniques” that could not be questioned. But it also started me on the road to finding the perfect posture, which obviously doesn’t exist in real life. Each of the 38 shodan katas work for everyone if performed correctly, but the posture, the “kamae” must be constantly adapted and constantly adjusted and forever scrutinized, and then re-adapted when everything changes, which it always will.

![]() For the classical warrior, during combat, a possible resolution of his problem would be suggested intuitively, and what was suggested was found to be worthy of retention in training when it yielded suitable results in combat.” (italics mine)

For the classical warrior, during combat, a possible resolution of his problem would be suggested intuitively, and what was suggested was found to be worthy of retention in training when it yielded suitable results in combat.” (italics mine)

Donn F. Draeger, Classical Budo

So in a way, it could be considered that “the way of the following foot” is a more efficient, more elegant way of saying “the constantly adjusting following foot, constantly searching for the perfect (and therefore impossible) posture which is constantly changing, requiring further readjustment.”

“Tsugiashi Do” is much simpler and will produce better results. Any professionally trained educator could tell you that.

And that’s the "onions" of posture.

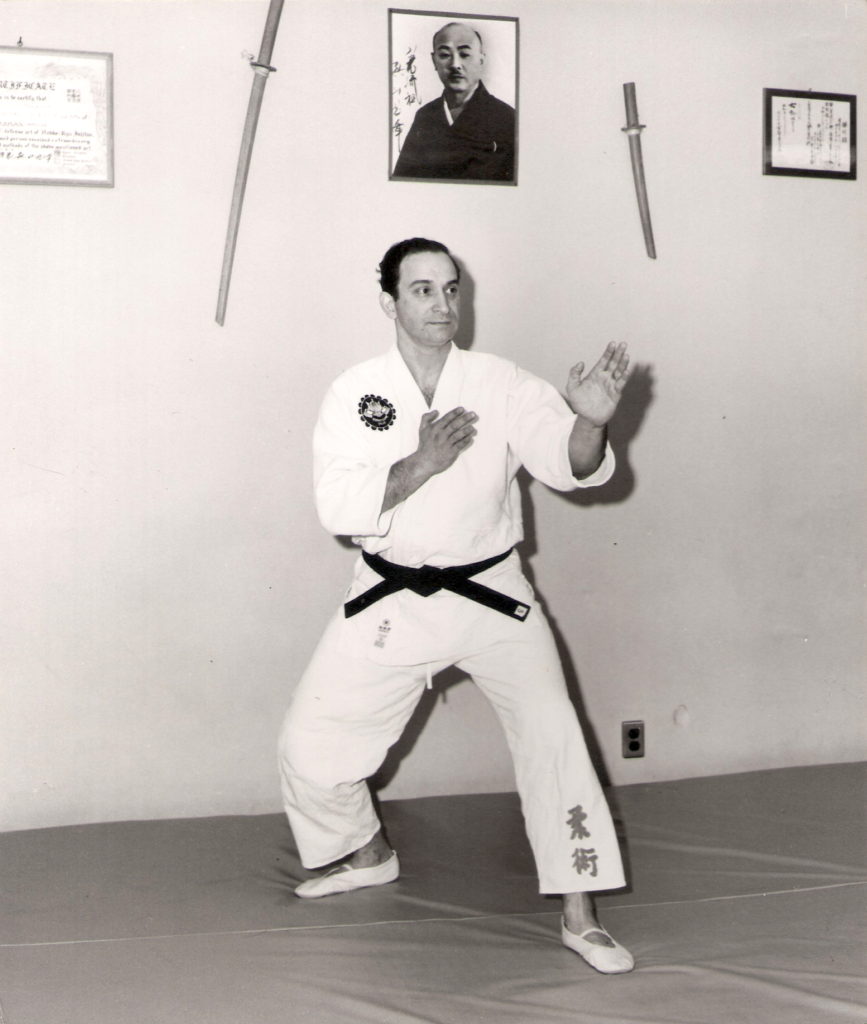

The Way it Was: Posture, circa 1968

Renoji Dachi stance considers the legs and hips as a pedestal upon which the upper body, arms and head are carried in a centered, balanced, upright posture. Movement is initiated in the feed, with interplay of the knees. Shita Hara (center of gravity), is lowered and may move in any direction while maintaining balance within the Renoji Dachi stance. The end posture of each step is identical to the beginning posture of that step.

Tsugiashi Do Ju-Jitsu Training Manual, Book One (1998)

In all forms of strategy, it is necessary to maintain the combat stance in everyday life and to make your everyday stance your combat stance. You must research this well.

Miyamoto Musashi, The Book of Five Rings (1645)

The more I read and study and think about posture and stance, and their big brother, Kamai, the more I think I don't know enough.

Thank you for reading this month's newsletter. I hope you found it interesting.

Next month: Hakko Ryu Takai 2018!