Welcome to July's issue of Shinbun!

It is the month of our Independence Day and the month that the tatami's (or mats) usually bare the sweaty prints of each roll and fall. This month's theme is The Dojo. The following are some thoughts, and some readings, and some memories of this concept of The Dojo. I hope you find them interesting and thought-provoking. I also hope to hear your feedback.

Faithfully,

Scot Lynch, Yondan, Tsugiashi do Jujutsu

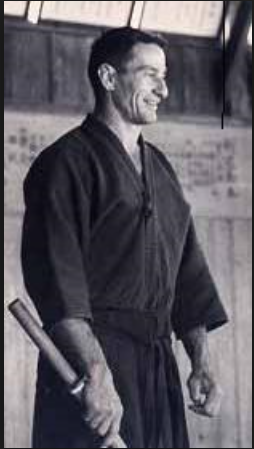

The author at Hombu Dojo, Omiya, Japan, 2000

The word dojo may be literally translated as “way-place.” The word implies that this is a place where the students will attempt to realize the ultimate reality of their chosen art. A school teaches techniques, as does a dojo. However, in a dojo, techniques are viewed as only a means to an end. The techniques must be mastered, but that is only the beginning, not the end, of study. The goal of a school is to teach a person new things; the goal of a dojo is to transform the person into something new.

From The Way and the Power

Hombu Dojo

Omiya, Japan, 2000

Jo means ‘a place.’ Do, of course, refers to a ‘Way,’ a discipline or art. A dojo, then, is a place for following the Way.

From In the Dojo, by Dave Lowrey

You can’t figure out Aiki or guess at it; it requires a teacher who literally takes you by the hand and shows it to you.

From Transparent Power, by Tatsuo Kimura

Tsugiashi Do Hombu Dojo, 1993

George Washington School

Edgewater, NJ

Dojo: A Place of Contradictions

A dojo is more than a place of learning, especially when that learning is, at it’s fundamental base, a teaching of the administration of violence. We punch each other, kick each other, we put each other in joint locks that make us cry out or tap out in pain, we learn how to dodge knives and swords and clubs. So why, aside from my home, do I feel that that the mat is the only place I go where no one’s trying to hurt me?

A dojo is a place where contradictions are managed. We are there to prepare for combat that might never happen, we learn from people who will likely not be there to lead us when that combat comes, and we practice against people with whom we have no quarrel. We put these people in pain, but we stop short of injury. We try to practice in a realistic manner, but we use precautions like dull knifes or wooden swords. We have to make sure we’re in a position to win against our opponents, but we want this victory and the violence associated with it to be a measured, controlled violence, and not “overwhelming force.”

This is very similar to military training, where dangerous skills are taught in the most realistic manner possible, where safety needs to be balanced with realism, but where winning is the absolute necessary goal. The junior people must learn the basics via memorization and repetition, and the senior people must learn the more abstract, nuanced skills necessary for leadership.

I would argue that it is no accident that Marines make natural martial artists. The ones I worked with in the Navy were compassionate, collaborative, and encouraging to a fault. And just like my fellow blackbelts, I would not recommend picking a fight with them. I would argue that it is no accident that the American who wrote first, and most intensively on the history of Japanese Budo and Bushido (and who is quoted in more martial arts books dedications than any other American) happens to be a former United States Marine, Donn F. Draeger.

I would argue that it is no accident that Marines make natural martial artists. The ones I worked with in the Navy were compassionate, collaborative, and encouraging to a fault. And just like my fellow blackbelts, I would not recommend picking a fight with them. I would argue that it is no accident that the American who wrote first, and most intensively on the history of Japanese Budo and Bushido (and who is quoted in more martial arts books dedications than any other American) happens to be a former United States Marine, Donn F. Draeger.

And I would further argue that it isno accident that the same person, General James Mattis, who once said to a potential adversary, "I’m going to plead with you, do not cross us. Because if you do, the survivors will write about what we do here for the next 10,000 years." is also the Secretary of Defense most rigorously opposed to enhanced interrogation. (General Mattis would be an excellent sensei.) These are not contradictions nor are they accidents.

To anyone who is not part of a Dojo, “No Better Friend, No Worse Enemy” may seem contradictory, but not to a jujutsu player. A dojo is where contradictions are managed.

Jesus Bonilla Jujutsu Dojo

29 Palms, California

While the learning and practicing of techniques (skills) in the dojo can prepare us for the physical action, the only way to prepare for the use of combative techniques in the stress of combat is to face that stress while training. This was well understood in the classical dojo, but it seems often to have been forgotten in modern budo.

From Koryu Bujutsu, by Diane Skoss

Dessert anyone?

I have tried out the entire spectrum of education, from vocational high school (to learn auto mechanics) to military technical training (to fix electronic gear) to a front line university education, and the closest I ever got to “Dessert” as we know it is a writing class. Sitting at a large table with a dozen or more students whose skills and talents were at least as good and mostly better than mine, and a published novelist and poet at the end of the table as professor, I would studiously avoid eye contact as I sat in front of my assignment, face down on the table, willing the professor not to call on me to read my work, knowing it would be judged not just by him (or her), but by my fellow students whom I greatly respected. Just like dessert. And like dessert, I mostly held my own…never to my satisfaction or to the full satisfaction of the professor. And like dessert, quite often my classmates, like my uki’s, had to look the other way when things didn’t go right. But just as in a good writing class, each piece is not a final report card. It is understood, by everyone, I would discover, to be a stop along the way. Just having the courage to read your piece out loud, disjointed or rambling as it might be, or stand in the middle of a mat, in front of your Sensei, in front of your classmates, with 3 seasoned, lightening fast blackbelts grabbing you, kicking you, punching you, when your gaukun, or your kata 1, is not quite serviceable, is enough. You have to pay your tribal dues. Proficiency comes later. Sometimes much later.

Entrance to Hombu Dojo, Omiya, Japan, 1999

(note the oversized American running shoes)

Good Reads – Decline of the Honor Culture

This month’s recommended read is not a book but rather an article, Decline of the Honor Culture, by James Bowman. https://www.hoover.org/research/decline-honor-culture

In my reading I had often found the word “honor” to be misused by the scoundrels of history, frequently providing moral air cover for abhorrent concepts like Chinese foot binding, the silliness of duels, and the killing or disfiguring of sisters and daughters who didn’t demonstrate appropriate chastity. But reading James Bowman has profoundly changed my views and made them far more complex and nuanced. “Honor” might just be more than moral subterfuge after all.

In my reading I had often found the word “honor” to be misused by the scoundrels of history, frequently providing moral air cover for abhorrent concepts like Chinese foot binding, the silliness of duels, and the killing or disfiguring of sisters and daughters who didn’t demonstrate appropriate chastity. But reading James Bowman has profoundly changed my views and made them far more complex and nuanced. “Honor” might just be more than moral subterfuge after all.

…the good that comes from membership in lesser but face-to-face honor groups, namely the sense of belonging, which always has come and always will come when people are able to say that these, but not those, are my people.

Professor Bowman’s article is a dire lament and an indictment of the 20th Century for losing sight of and appreciation for, honor, especially in the United States:

Loyalty, courage, and self-sacrifice, which commonly take place in relation to a group, are thus downgraded as virtues while toleration, nonviolence, and social inclusiveness become the preeminent virtues.

As practitioners of martial arts, we have to grapple with the dichotomy (a.k.a. “hipocracy”) of respect for authority of knowledge, adherence to forms, and care for others’ well-being and pain, while simultaneously learning how to, ultimately, hurt people. To many this would seem schizophrenic. But this is no more schizophrenic than the fact that we call our fighting forces our “Defense Department” or that the word Samurai is derived from “One who serves.”

For an understanding of the rival claims upon us of honor groups goes naturally with the military understanding of honor and those in the military will doubtless recognize the phenomenon of overlapping and sometimes conflicting honor groups with compelling claims upon their loyalties. The country is of course the ultimate honor group and the one that military men are pledged to serve, but lesser loyalties are not abolished by that pledge, and the other honor groups that service to your country involves—your branch of the service, your ship or post, your unit or your status as officer or enlisted man—are generally seen as complementary rather than contradictory to it. It is the rare instance in which men of honor have to agonize about what others might think of as these conflicting loyalties.

Hai, Sensei.

In a space where focused, controlled and regulated violence is the object of the game, where all preparations are made for future but hypothetical combat, there are risks and responsibilities that demand a sort of loyalty to the group. With that loyalty comes a heightened wariness of those (friend or foe) outside the group. Newcomers must be watched, deemed safe (to us) and loyal (to the style and to Sensei). This is for the safety of all involved and the health of the group. The leader’s ability to maintain cohesion of the group, as the group grows or shrinks, determines the viability and longevity of the group and whether it will indeed become an “honor group.”

Some leaders must extend the honor group. General Stanley McChrystal, in his book Team of Teams, refers to this as extending out, as far as possible, the precise line where everyone in side the line has true shared purpose and loyalty to the mission, and “the point at which everyone else sucks.” (page 126) It’s simply a managerial method for enlarging honor groups which McChrystal had to figure out to kill Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. McChrystal figured out how to create and grow honor groups at scale and at speed and killed some of the nastiest enemies (of everyone). The fact that McChrystal was fired lends uncomfortable legitimacy to Bowman’s argument that honor, well, just ain’t what it used to be.

But part of belonging to an honor group (like a dojo) is to commit to being judged and to make sacrifices.

Honor groups do judge us, I’m afraid, and often in stark, black-and-white terms. If we don’t like being judged, whether for good or ill, we’re likely to avoid them.

Bowman says Facebook is a group that does not judge, tells you exactly what you wish to hear, and asks nothing of you, in many ways the polar opposite of a dojo. When I knelt across the mat from Sensei, and heard what we were going to be doing that night, I knew that something was definitely going to be asked of me. Submitting to that is to become part of the fabric of a dojo.

But Bowman provides a statistical analysis in the article that haunts me. In 1969, during the Vietnam War, my home state of New Jersey contained, out of all the 50 states, the largest percentage of veterans. In 2007, New Jersey was 50th out of 50, having the lowest percentage of veterans of all the states. And this was my state. My “group” which had a front row seat to the Greatest Generation has somehow decided to sit home and comb through Facebook while other states are enlisting. Bowman explains that we are slipping into a worrisome situation were military membership is increasingly reliant on certain states for its numbers, and that this is a direct reflection on the decline, during the 20th century, of honor groups and their function in society.

On Wednesday, January 16, 1991, class started the usual way and we practiced and trained as usual. But at 9:00, roughly half way through the class, Soke Sensei halted us and put as at han tachi (on one knee) and announced calmly that “Our President has something to say.” He plugged in a small black & white television and with a little adjustment of the 2 antennae, we watched a very grainy and splotchy George Herbert Walker Bush announce the beginning of air strikes against Iraq and why they were occurring. When the announcement was over, our Sensei turned off the television and without comment, put us all back to work. His opinion of the war I was waiting for never came. I think because Soke Sensei was not making a statement or putting on a show. It wasn’t complicated. When you’re in our honor group, and the leader is putting that group at war, you listen to what he has to say. That’s simply what you do when you’re part of the group.

On Wednesday, January 16, 1991, class started the usual way and we practiced and trained as usual. But at 9:00, roughly half way through the class, Soke Sensei halted us and put as at han tachi (on one knee) and announced calmly that “Our President has something to say.” He plugged in a small black & white television and with a little adjustment of the 2 antennae, we watched a very grainy and splotchy George Herbert Walker Bush announce the beginning of air strikes against Iraq and why they were occurring. When the announcement was over, our Sensei turned off the television and without comment, put us all back to work. His opinion of the war I was waiting for never came. I think because Soke Sensei was not making a statement or putting on a show. It wasn’t complicated. When you’re in our honor group, and the leader is putting that group at war, you listen to what he has to say. That’s simply what you do when you’re part of the group.

We rei’d out normally that night, had tea at Billy B’s, and went home. As I rode my bike through Harlem that January night, on my way home, I did not struggle to figure out who I was or how my cascading honor groups were structured or where and how I fit into them.

The onions of a Dojo: Empathy and Honor

Being in a dojo allows the students not only to work with sensei face-to-face and hand-to-hand, but it also allows the students to observe sensei’s working with each other, and this can sometimes be more instructive (and a lot more fun) than feeling a good koto gaieshi. One such time was in the Wittenberg brothers’ Hillsdale dojo. Bill Dempsey, a very popular and personable Shihan was working with us and it was time for dessert. It was the late 1990s and Soke Sensei and Shihan Bradle were working with Shawn Wittenberg on yondan technique. (I know this because I was his main uke and had to stop in at the seven eleven on the way home to get a sugary soda and a chocolate bar in order to stop my hands from shaking on the steering wheel. But that, as they say, is another story.) Shihan Bill Dempsey took a turn at dessert and attempted to perform one of the techniques Shawn Wittenberg was working on. I was his uke and he was having difficulty. (He was definitely not, to be clear, having any difficulty putting me in great pain.) But he was having difficulty with the precise move he was attempting. The look of frustration on Bill’s face was unmistakable and just as the situation was getting awkward for me, Shihan Bradle (the second most dangerous man in the room, after Soke Sensei) gently moved me out of the way and took my place as uke. With a combination of empathy, focus, and firmness, Mickey said “You can do this Bill.” He proceeded to make adjustments to Shihan Dempsey's technique, and said some “sensei things” I did not understand.

Although I had bounced around a number of dojos and taken my share of falls, that night I learned that a dojo is not just a place with a wise and powerful sensei sitting on the other side of the mat tells you what to do. It is where competition and success are important but still take a back seat to loyalty to the group. That night I learned that a dojo is a sort of honor culture, where peers and partners say “I trust you to judge me” and “I will take the risk of failing.” And I also learned that a dojo is also a place where that trust is reciprocated, where commitment and partnership is on full display. Shihan Bill Dempsey, who had been quite out of practice and had had some health issues, was dangerously close to losing face in front of his honor group. Shihan Mickey Bradle could not permit that to happen. No better friend, no worse enemy.

Although I had bounced around a number of dojos and taken my share of falls, that night I learned that a dojo is not just a place with a wise and powerful sensei sitting on the other side of the mat tells you what to do. It is where competition and success are important but still take a back seat to loyalty to the group. That night I learned that a dojo is a sort of honor culture, where peers and partners say “I trust you to judge me” and “I will take the risk of failing.” And I also learned that a dojo is also a place where that trust is reciprocated, where commitment and partnership is on full display. Shihan Bill Dempsey, who had been quite out of practice and had had some health issues, was dangerously close to losing face in front of his honor group. Shihan Mickey Bradle could not permit that to happen. No better friend, no worse enemy.

That’s the onions of a dojo.

Yoshitsune Dojo

Closter, NJ, Circa 1982

The Way it Was: The Brothers Wittenberg

Shawn Wittenberg performing Moshimawari during Sandan promotion demonstrations

circa 1990s

Before I enlisted in the Navy, the Wittenberg brothers were my classmates. I got my first color belts from Shihan Doc Cohe, they got their first belts from Mike DePascuale Jr. When I left the Navy, Shawn was a Brown Belt and Keith was a Blue Belt. But they were always a bit more than their belts. Shawn always had a gaukun that felt like a tazer on my wrist, and Keith always had an unnatural ability to shapeshift his balance points such that whenever I thought I knew how to throw him, his balance point was somewhere else and he would just stand there smiling at me.

Later, they ran the dojo in Woodcliff Lake, NJ that got me ready for my black belt. Soke Sensei would come up from Maryland each month to do a weekend seminar. Shawn and Keith both ran several classes a week, and they both seemed better than they should be at their levels.

Later, when I was getting ready for nidan, after the Woodcliff Lake dojo had closed, Shawn and Keith and Mike Wilson (Keith and Mike were preparing for sandan) met Monday afternoons in the sweltering weight room behind the Hackensack, NJ dealership. Shawn’s gaukun was even more powerful, but now Keith’s gaukun was that good as well. Still, somehow better than I reckoned they should have been.

But if I look back at the early 1980s, all the clues were there. I took Shihan Doc Cohe’s Wednesday night class and passed on what I used to call the Tuesday/Thursday “Commando Class” taught by Mike DePascuale Jr. In this class, the standard was to do 45 minutes of “backfall, get up, double-punch, kick, then backfall again” before beginning the class. (A lot was asked of them.) Somehow I had other things to do on those nights. Shawn and Keith did not. They were there, doing the backfalls and the ukemi, the punches and the kicks.

In a true dojo (unlike most other places), things make sense, and there are no accidents. My theory of the dojo is that the people with the most mat time, backfalls, seminars, practice time and study, are the most talented. And the most talented person in the room is the guy kneeling seiza in the middle. The second best guy is the one sitting to the first guy’s right. The 3rd best guy… and so on and so on. If anyone ever challenges my theory of the dojo, I will defend my theory with the Brothers Wittenberg.

July 9, 2019

Ah! The good old days with Shawn and Keith, Pain, Pain, and more Pain! Never enjoyed myself so much! Very good Shinbun Sensei.